Welcome back to Triathlon Science, your go-to source for the latest research and insights to elevate your triathlon performance. Today, we’re delving into carbohydrates and fat adaptation training, exploring the science, strategies, and nutritional aspects that can transform your long-distance triathlon experience.

In this post, we’ll unravel the mystery behind fat adaptation training, which involves restricting carbohydrate intake before, during, and after exercise. This training aims to shift your body’s primary fuel source during exercise from carbohydrates to fats, ultimately enhancing your endurance and performance on race day.

Before we dive into the details, let’s address a fundamental question: why shift from relying on carbohydrates to utilising fats as an energy source during long-distance triathlons? Carbohydrates, while an efficient energy source, have limitations—the body can only store enough for about 90 minutes to 2 hours of moderate to high-intensity exercise. For races lasting longer, like marathons or Ironman triathlons, athletes often resort to consuming carbs during the race. However, this method can lead to gastrointestinal distress, affecting performance and getting it wrong can cause athletes to ‘hit the wall.’

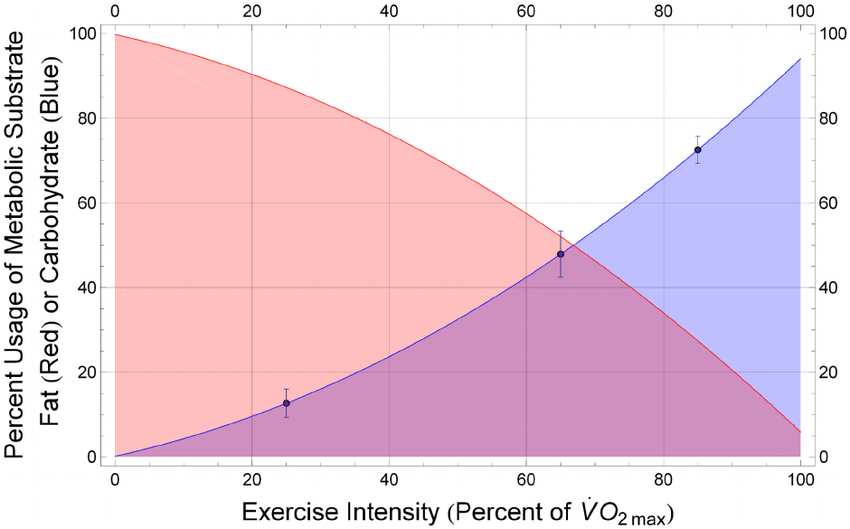

Understanding the body’s utilisation of carbohydrates and fats during exercise is crucial. Carbs are quickly broken down by the body into glucose and stored as glycogen, and serve as a readily available energy source. On the other hand, fats are stored in adipose tissue, and provide a more energy-dense fuel source. Even the leanest athletes carry enough energy in their fat stores to complete an Ironman triathlon. When an athlete exercises, the body will always use a mix of carbs and fats to provide energy for the body. There will never be 100% fat or 100% carbs as an energy source. As the intensity of exercise increases, the body will increase its reliance on carbs for fuel due to carbs being more oxygen and time-efficient for the body to process. At a maximum intensity exercise the body will use close to 100% carbohydrates. See the below graph which shows how the energy substrate (type of fuel) changes as exercise (measured as VO2max %) intensity increases.

While the prospect of using fats as a primary energy source seems appealing, it comes with challenges. Fats, being more energy-dense, take longer to convert into usable energy. Imagine your cells as a suitcase—carbs are like hastily packed clothes, easy to store and retrieve, while fats are meticulously folded garments, requiring more time and effort to pack and unpack. Converting fats into energy demands approximately 25% more oxygen consumption and is slower than carbohydrate oxidation.

Fat adaptation training is rooted in the belief that the body can adapt to different metabolic demands. Three main strategies have been explored:

- High Carb Availability Diet: The conventional approach for many athletes involves regular carb consumption, constituting about 50% of their diet with the rest made up of protein and fats. This includes carb loading before races and supplementing with carbs during extended periods of exercise.

- Periodisation of Low Carb, High Fat: This strategy involves alternating between low-carb, high-fat (<10% carbs) during base training and high-carb intake before races. However, studies show no significant advantage over a consistently high-carb diet for races under 90 minutes. This is because the body will use the stored glycogen in the muscles and liver to sustain a high intensity. The longer the race, the lower the relative intensity that can be sustained throughout.

- Low Carb, High Fat with occasional Carbs: This method combines a low carb, high fat diet with targeted carbohydrate intake during high-intensity or quality workouts. The goal is to enhance fat-burning capacity while preserving the ability to use carbohydrates effectively by consuming carbs weekly. Personally, this is the method that seems to work best for me.

In this next section, we explore fat metabolism during endurance triathlon. Studies show that athletes who undertake exercise in a low-carb state optimise their fat oxidation and improve the body’s capacity to use fat as fuel. It’s important for athletes practising low-carb training to include a weekly high-carb workout to maintain the body’s capacity to absorb and oxidise carbs without gastrointestinal distress.

The “train-low (carb), compete-high (carb)” paradigm is an effective approach to improving fat oxidation, where athletes train under low-carb conditions and then restore carbs before and during competition. This approach involves training for 5-14 day with a low-carbo, high-fat diet followed by a 1-3 day high-carb diet before a race.

There are challenges associated with restricting carbs before, during, or after endurance training. These include difficulty in maintaining high training intensities above 90% Vo2 max and may cause gastrointestinal distress. Because fats take longer for the body to break down and they require more oxygen to process, the body no longer has this oxygen available for the muscles to use and thus athletes will experience a reduction of performance when exercising at very high intensity. However, a study published in 2023 found that a low-carb diet did not reduce 5km time trial performance in runners compared with high-carbs athletes after 5 weeks of low-carb diet. This demonstrated that a low-carb diet may not hinder performance for athlete’s competing in shorter races. However, there is substantial research that shows as the intensity of exercise increases, so does the proportion of carbohydrates used as fuel, so the athletes competing in a 5km time trial would likely have been relying on carbs as energy in this study.

Moving on, let’s talk about a twice-daily training model. Athletes will perform two sessions and restrict carb intake during, and between sessions. Studies show that this increases fat oxidation, forcing the body to use fats instead of carbs for fuel during exercise. This is another effective way for many triathletes to adapt to using fats because triathletes will often train two disciplines per day. Consuming adequate calories and nutrients from protein and fats between sessions is important to avoid falling into a caloric deficit which will vastly increase injury risk.

The takeaway from this research is that a low-carbohydrate, high-fat diet may be useful for people doing ultra-endurance events or constantly having gut issues from consuming carbs during physical activity. Training with low-carb availability forces the body to use a higher proportion of fats for fuel, and results in the body adapting to burn fats more efficiently. It can take 2-5 weeks for the body to adapt sufficiently to use fats during races, and even then, it’s important to consume high-carbs once a week to maintain the body’s ability to oxidise carbs. During races, it can be important to consume some carbs, as they have been shown to stimulate digestive functions. Finally, every athlete is an individual and will require trial and error to find a strategy that works for them. Perhaps trial a low-carb diet during your off-season and see if it’s for you.

Leave a Reply